SNP Episode 108 - Rashaun Rucker

SNP Episode 108 - Carolina Red Clay w/ printmaker Rashaun Rucker

We’re kicking off a new season of Studio Noize with artist and printmaker Rashaun Rucker!

Rashaun recently debuted a new body of print work called Up From the Red Clay at M Contemporary Art in Detroit. In a series of linocut prints, monoprints, and drawings Rashaun prints the stories of his family. Using photographs from his grandma he reveals the layers of history, life, and love that exist in Warrenton, NC. JBarber and Rashaun reminisce about living in rural North Carolina and get into all the printmaking nitty-gritty details.

Note: Studio Noize is produced for the ear and designed to be heard. If you are able, we strongly encourage you to listen to the audio, which includes emotion and emphasis that's not on the page. Transcripts are generated using a combination of speech recognition software and human transcribers, and may contain errors. Please check the corresponding audio before quoting in print.

Jamaal: Alright, yeah so, Studio Noize, we back with the fam, Mr. Rashaun Rucker, coming back to the podcast. What's up, man?

Rashaun: What's going on man? Glad to be here, I love coming on Studio Noize and chopping it up, you know it's just like talking to old friends.

Jamaal: That's right, yo, you the fam. So, my man, I've been down in my thesis for a little while but now we back man, this whole time I've been gone man, me and you've been talking and you've been working on the show “Up from the Red Clay”, debuted at M Contemporary Art in Detroit, March 26. It'll be the-- it'll be up till May 1 so you'll get-- you can catch-- after you listen to this episode, you can catch a little bit of it before you get that. But don't worry, it's already sold out, all you could do is get on the waitlist for the next one. Yeah man, so, how did you feel when the show went out man?

Rashaun: Oh man, it's funny because I always tell people when you work in your house like I do, you work in the house too and it's like, you working on pieces, and they kind of just stacked up on top of each other, you can't get a vibe for it. So, you know, I took the work to Melanie at the gallery, I dropped it off, and then she took it to the framer so when I came back in the day before the opening, they had hung it and I was like, "Oh snap.".

Jamaal: Looked completely different.

Rashaun: I was like, "This looks real good.", like, because you get a different vibe when you see it framed and hung. Like, man, at my crib, I'm working like, I basically turn my living room into my working studio then turn another room into like the living room so, when that stuff is stacked up, you know when I'm carving that stuff, you got linoleum everywhere, you know? This is like, you can't really get a real feel for it.

Jamaal: Yeah. Put them on white walls, they cleaned it up.

Rashaun: Yeah. And it was like a little--, it was like a process to feeling really good about it because you go from carving it, you feeling good about the carving, and then you go to printing it, you feeling good about the prints and when you see the framing and you see it hung, it's like, "Okay.", the whole triple thing, the effect that came in.

Jamaal: Yeah, that's it right there, you need that last piece man. I always tell artists, that presentation, man, you got to focus on that presentation, it does half the work for you already.

Rashaun: Yeah, man, I'm a stickler about that, about how things are hung and how they're presented and framed. And printmaking is just so fickle in itself, even though I have a love affair with it, it drives me crazy because like, I think I'm just like so heavily focused when I'm doing. I'm carving because as you know, bro, one false move.

Jamaal: That's it, yeah.

Rashaun: Done deal, start all over again.

Jamaal: Start a new piece. I know that's right, but that's also the thing about printmaking that I love is that you got to work it in, you know what I mean? Because no one stroke will ruin it, so you can still get time to like, mess it and make it seem like you meant to do it. And then, like I always say man, if you never tell anybody was a mistake, everybody thinks you are a genius.

Rashaun: I can go to every carving and point out 10 bad marks, like you said, you have to figure out how to camouflage it, how to work with it when you do make a bad mark. Like, "How can I make this work now?".

Jamaal: Yeah, we got to be loose when you're doing carving because like you said, it's permanent. Like you take that wood out, it ain’t no real way, I mean, you can glue it back in if you feel like it. It's hard and you still see it, you know? When you print it, you still see it.

Rashaun: We see it, I don't think the person in the gallery sees it, but we see it. We be like, "Man, that's why I took that chunk out.".

Jamaal: It's like a bright red light. Yo, I'm gonna read this from your catalog man, you got Juana Williams, more Studio Noize fam. What's up Juana! For everything that she does, she wrote a nice little intro essay for you, I'm gonna read this from it, "From the red clay of North Carolina, black stories have been birthed and woven through time and distance, through tragedy and triumph, through whispers and yells, through church pews trains, cars, doffing through birth again. Up from the red clay is a conversation between Rucker's past self and future self, his family who lived and passed on, his family 1000s of miles away, his sons and future generations.". That's powerful stuff man. Juana, why you never write for me like this? Like, I need something written like that, that's pretty tight right there.

Rashaun: Bro, it's funny, I didn't know you were gonna read that part but that's the part when I read the whole essay, that part hit me like a sledgehammer like, "Woah.".

Jamaal: Yeah, that's the hit, man, that's that filling man, that's the filling right there.

Rashaun: Yeah, like, look, the funny thing was, she sent me the essay and was like, "Yo, it's finished. I want you to read it.". Bro, I text her like midnight, I was like, "I know I shouldn't be texting you this late. This is dope.". I felt like a whole vibe. Like, I was like, "Man, I can't believe she did this.". Like, it's just that good so, I was excited that you even pulled that part out of it,

Jamaal: Yeah, we were talking about Juana and I was asking you like, I was saying that, when you're working, you don't even see what all the work looks like so, when somebody sees it, like, all they see is the finished product and like, you can see all the little connections that are in between it from all the different pieces and while you're working, you don't see it. So, like, what was it like getting Juana to put that in words for you?

Rashaun: Boy, it was incredible. Like, she sent me that essay and I told you, it was like late at night, and I read it, I'm like, "Man, I know I ain’t supposed to call nobody at midnight, but I text her like, "Yo, this is incredible, this is amazing.". Because it really bought together all my thoughts, and we, you know, we talked about it, but like, I mean, she's a great curator and writer like we didn't-- we talked about it but man, like when I saw what she wrote, I really felt like she captured me. It captured the body of work I was trying to produce.

Jamaal: I think so too. And I think she connected a bunch of the different threads that you had going on too, like, especially that part about talking to your past self, you know what I mean? Because let's take it all back. Where's the inspiration for this show, man? You say you used to spend your time in Warrenton. Anybody know Warrenton, Littleton, North Carolina man, that's what we talk about. It's two Carolina boys on the podcast today giving it up. Like, so, tell us about what was it like back in Warrenton man?

Rashaun: I mean, so I was born in Winston-Salem, but my dad's side of the family is from Warrenton and so, I would spend a lot of time in Warrenton, holidays, summers. And Warrenton was just like, man, it just felt like love, even though as a place, it was stuck back in time. You know, something, when you talk about like social issues and things like that but just, my family there felt like love like, it was just warm and encompassing like, you know, you're talking about helping your granddaddy fix the lawnmower or, you know, watching your grandma, you know. Watching your grandma and your aunties like shell beans and all that other stuff. Like, you know, drinking their tea on the porch, you know. That was a type of, you know, vibe that it had, and I tried to kind of recreate some of that in the work. But like, man, living in Warrenton was like, you know, I will work in my granddad's family business and then in the evenings, me and my cousins, we who would go fishing for bluegills, go catch crawfish, you know, and it was just like, I felt like-- it's funny because you remember that movie? Stand by Me?

Jamaal: Yeah.

Rashaun: With like, the kids are on these trips, I feel like that's how me and my friends and cousins were living like, you get on a bike and you, man your parents don't even know or your grandparents. You're on a bike, you're 6-7 miles away from the house on a bike with your friends like fishing at a pond, just riding, just living that life. And it's like, I remember bro, we would go like, we would make some bologna sandwiches at the crib, stop by the store, get anew grapes or peanuts, and a pack of nabs and like, ride our bike somewhere to go fishing and probably-- we would just stay out there all day, listening to my little music, you know, eat my bologna sandwich, drinking that chill wine and watching out for snakes.

Jamaal: That's the life man. That's the life.

Rashaun: Bro, they don't know nothing about like, some of them do but it's like, bro, we would go fishing sometimes and get rags and dip them in kerosine and tie them around our ankles to keep the ticks off of us.

Jamaal: You always got to check for ticks when you finish man because they'll get on you.

Rashaun: My grandma used to be like, she had a back porch, she'd be like, "Man, y'all take off your clothes back there and look for ticks before y'all come in this house.". Yeah, she didn’t want them bugs in the house.

Jamaal: That's good, fun times, man. Yeah, riding the bike, how big was your family like around there? That's a weird question because you know, in North Carolina, like everybody's family, like somehow, you connected to somebody all the time. So, it'd be about 100 people that are all related.

Rashuan: It was a big family and actually, like what I saw was lasting probably typical of Warrenton and Littleton area like, we all lived around each other. So, at my great grandparents' house where I would stay most of the time, my great aunt, which was my great grandma's sister lived next door, her brother, uncle, lived across the street. My grandma and granddad live probably a mile down the street, my uncle Leo probably a mile down the other way. Like, everybody stayed pretty close to each other, everybody pretty much stayed on the Baltimore road.

Jamaal: And you would just pop up at somebody's house like it was your house like you know what I'm saying? That's that feeling of family when you talk about that love man. Like, it's the togetherness that you had.

Rashaun: Bro, we would sit on a porch like this is another one, we would sit on the porch and drinking tea and helping my grandma like you know snap beans and stuff and it was like, bro we would do that all day and just wave at everybody who drove by and they will wave back. And grandma would be like, she gets mad if I didn't wave, she's like, "You see that man waving at you?", I wasn't even paying attention, I'll miss a car or two. But the funny thing was some people would just pull over, bro, they wouldn't even get out to the car, they would just pull up to the front of the house and be on the side of the road now by the ditch, talking to my great-grandma through the window.

[Cross talk]

Rashaun: Or sometimes they would pull over and have some-- I had a cousin Eddie who was a farmer who lived down away, he would pull up almost, at least twice a week. He'd yell and be like, "Hey Sal. Shaun come out here and get these collars for your grandma.", he said, "They came good this year, I got more than I need.". So, he would always bring stuff that like grew double or triple, whatever he thought, you know because that was his job was like he will sell vegetables on the truck so, he will pull up. You know, one of the prints I didn't get to do but it was like, one of the things I think about all the time was like, at my aunt's house next door, my great aunt, it was like this big oak tree and that's where all the men used to gather, they'd be drinking beer and telling a story, they'd be like, listening to mud bone or something like I would go out there as a kid and just sit around because I wanted to hear the craziness. And sometimes they'd be out there, man, it'd be four or five and they all in a car with the door open, sitting in the car, talking, they're not even sitting near each other. they're sitting in individual cars, talking. Or, they sitting in a broke down car that somebody used to have and that's like, you'll just go out there and be like, man, they're in there smoking and drinking beer like, in a broke down car and I'll be in the backseat and just be ear hustling. I would think those were the greatest stories I ever heard, bro.

Jamaal: Yeah, because that's that real-life man, there was a lot of real-life, a lot of knowledge being spread, yo, and just, you know, the way we relate to each other, you know what I mean? It's nothing like that, that down whole country talk that you get to somebody else, man and that's kind of genesis for the series man. I know you say you got some pictures from your-- your grandma sent you a bunch of pictures, like, tell us about that.

Rashaun: Yeah, she-- so, I wanted to work on-- I mean, I've been thinking about this series that we're making for like, probably two years and just every time going to my grandma's house and watching like, she always had like a bunch of photo albums and a footlocker full of photos and I have been telling her about what I wanted her to do and eventually, you know, even though COVID, she eventually was able to get around and send me pictures, she probably sent me like 3 or 400 pitches and I kind of used that as source material and like-- so, the day I got them, I started going through, editing and you know, putting them in piles like this might work, this might not work, you know, this definite no. Then, I went and bought about 12 photo albums and organized all of them, and then I had like one photo album that was like, this is the photo album I'll work from completely. So, it was cool, and it was also cool man, not even from the standpoint of necessarily making work but just to be able to go through your family's history visually like that, to be able to see people like you didn't even know bro, like, you know, you'd be like, "Man, this is insane.". I mean, one of the things I didn't get around to doing either because it just became a time crunch was, there was a picture from the 1940s of my cousins, like eight men and they founded a church in Louisburg and it was like, I wanted to do that picture, but I knew it was gonna be like a five-foot carving. So, I was like, "I'm gonna get back around to that at some point.", they all got like black suits on, white shirts, black ties.

Jamaal: Oh, yeah, that's made for a print right there.

Rashaun: And four of them, they were sitting in a chair with they legs crossed and the other four standing behind but they all brothers, but they are cousins.

Jamaal: That's an awesome picture right there. So, how long do you think that-- what's the timeline on these pictures? Like, if they got one from 1940, is this all the way till current, or was this back when you were a child?

Rashaun: It just went from 1942 to the present.

[Cross talk]

Rashaun: My great grandfather working at the Texaco station in 1942, he used to be a mechanic at the Texaco station and pump gas for people when they would pull up. And it's crazy because I never-- I didn't do that piece because I actually commissioned another artist here to do-- to produce that piece for me in their own vibe but my grandfather had like the zip-up, you know, the one-piece zip-up suit, mechanic suit. He had a shirt, and he had a bow tie on, a shirt, and a bow tie with a little-- it looked like a police hat, but it had the Texaco symbol on it. And that's what he was doing, he was a mechanic at Texaco where he would do small engine repair and he would like pump gas because, you know, back then, most of the service stations with like full service.

Jamaal: Yeah. Full service, yeah, they check your oil and everything.

Rashaun: Yeah, that's what he was saying, "I used to check people oil and windshield wipers, and I might wash the windshield for them and put the gas in and they'd be on they way.".

Jamaal: Yeah, that's crazy.

Rashaun: There's still a couple of joints around me like it's funny, it's like one around me with the full-service joint.

Jamaal: Yeah, that's old school right there, man. So, how many, in all, how many family members do you think you covered in the course of the show?

Rashaun: Probably 20.

Jamaal: 20? How many-- tell people how many pieces in the show?

Rashaun: I think there were 22 different works in the show.

Jamaal: And that includes the relief, monoprints in it?

Rashaun: Two drawing, two collages, relief and monoprints.

Jamaal: That's what's up, man. Now, one thing we didn't-- I didn't ask you is, you know, they can go back and listen to the last episode where you got your American Ornithology series was graphite drawings of men and pigeons in all the contexts that come with that so, why was this idea meant for printmaking and not drawing?

Rashaun: Dude, you know, I got like this weird thing, and I don't know why I do it but like, a lot of times when I'm making work about my family, it's almost all printmaking because it's almost all about the rural south and for some reason when I think printmaking, I just think south, like I just think, I don't know. It's like the folk story behind it and to me, printmaking is very, is rugged, you know, you work and you're redacting things you know, it's like physical. And when I think about it, I think about the hard work that we talked about, you know, shoot, half the man I knew was working at sawmills and paper mills. You know, I told somebody that you would see dudes and their shoulders will be completely scarred up because they would be carrying logs at the pug wood factory for a living and it’s like, when I think about that, for some reason, printmaking and the physicality of it always kind of encompasses the work I do about my family.

Jamaal: Yeah, and it feels older, right? It feels weathered, you know what I mean?

Rashaun: Yes.

Jamaal: Yeah, it has that-- the chatter to it, you know, if you ink it right, it has like that little bit of noise in it. It is something about that feeling, it feels like, you know what it feels like? It feels like when those illustrations from a Bible, it feels like that type of stuff. Like, it's a history that's being told.

Rashaun: And it's funny because even though of course, we know there are printmakers, I'm a printmaker. You're a printmaker. We know plenty of printmakers, but every time people come to a show, they're like, "I don't ever see printmaking no more.". So, it is something like cool about it that is not necessarily a thing that is done on time.

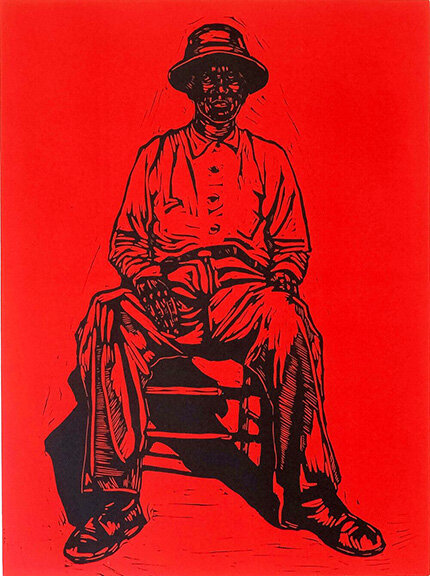

Jamaal: Yeah. It's a physicality like you said that's involved in it. So, I'm gonna jump into one of the prints, man, one of the first ones I think you might have shown me was Burdens Down Lord. I see a man sitting on a stool, like tell us about this picture and tell us about the process.

Rashaun: That was my great uncle John. I think it was from 1949, and it was him sitting in front of a shotgun house but for the drawing I actually took the house out and just drew him and called it Burdens Down Lord because I just thought about like, that was like his house and his land and I just thought, "Man, like, what was he going through being black in 1949 and being proud of that shotgun house, and like finally having something of his own.". So, when I saw him sitting in the chair, it was kind of like his body kind of gave off that thing, like, Burdens Down Lord, like the old song like, "Lay my burdens down.", you know, if you know that song, it's like you know, the next line like, "I feel better, so much better.". And so, since I laid my burdens down, so, that made me think about it like a lot of this stuff was built just on church and going to church a lot in Warrenton, and just thinking about how that gospel music and those hymns kind of interacted with the titles and the themes and the work that I wanted to do because I knew how Uncle John had struggled to get the shed proper, he had done all the work that most black people in America had to do and that picture is just like, gave me like, he had like the look of satisfaction, sitting in that chair.

“Burden Down Lord” linocut by Rashaun Rucker

Jamaal: Right. He got him some land.

Rashaun: Yeah, he got this look of rest about him. Like, "I got a house and I got, like some semblance of satisfaction and normalcy.".

Jamaal: Yeah, me and you talk about it all the time, it's like, sometimes we think about the people back home and it's like, in terms of dreams, like we had dreams of being artists, like, they had dreams to get them some land. You know, that was like the pinnacle, like, "Oh, man, you got you some land?".

[Cross talk]

Jamaal: You done made it!", that's what they used to think man. Like, "You got you some land? That's the ultimate, yo, it can't get no better than get you a couple acres.", you know?

Rashaun: Man, I remember folks like, and it left an impression on me, I remember folks talking like that. I remember folks saying like, "Johnny done built him a house, he built a brick house too.". I don't know, having a brick house was like a huge thing, and you know, it's like, you know, and it just kind of gave me that type of vibe, looking at that picture of my great uncle. Yeah, a lot of those men I knew, you know, back then, they were also brick masons, they were building their own houses, doing all these different things and I can't tell you the amount of people I know who built their own house.

Jamaal: And, you know, on one hand, you had to, right? Because now we talk about these little towns, it's like, it’s not like Atlanta now, like, you can find somebody to build your house, like, it's mad people, contractors that'll build you a house, everybody got an LLC, and they can do stuff to your house. But I mean, you're talking about a Littleton in North Carolina, it might be 1000 people, like counting the kids, like in the whole town. Like, what's the odds you're gonna have like one or two people like even two people that would have the skills to be able to build you a house? So, a lot of this is, you got to make a way out of no way.

[Cross talk]

Rashaun: I think Warrenton like, I gotta look back but I think, when I last saw was like 1400 people and in my mind, I'm always like, "It can't be that small.", but it probably is.

Jamaal: Yeah, it probably is. Yeah.

Rashaun: I just don't ever feel like it's that small, but you're right. It's like, I had a Cousin Charles Davis and he was a contractor, he lived in Warrenton and it was like the few people who were like legit contractors, they were doing like real work in like Raleigh and Dime like, they wasn’t doing work, they were like-- he mostly did his work in the cities, he just lived in Warrenton. So, like when you say, you know he was doing that and then I think what happened was like people who had that skill set, they were cooperative and amazing, they built their own houses, but they built them like on they off time you know. I would see a dude build a house for like 2-3 years because he had a regular job and, on the weekends, you know, him and his homeboys get together and you know one might be a brick mason, one might be a carpenter, one might be a plumber, they just, piece by piece put the house together.

Jamaal: Yeah, we used to do that with portraits and shares, like, "You need to share? Like, the weekend after next because I ain't got nothing to do.". You know, then we get together and put it together you know because it was a community, man. There was this whole point where nobody's coming like this is us, like this 1000 people are all the people that we know so, you know, between us like either you do not have a porch, you're gonna keep that hole in your steps or somebody's got to come and help you, you know what I mean? Because eventually you know, you're gonna need help. And it's that whole sense of community man that is missing a lot of times in a lot of cities.

Rashaun: And that's what the work is about, like, you see the dudes pull up in they car with the concrete bags in the trunk and the five-gallon buckets that mix with it and maybe a brick mason, he'll just jump out and be like, "Man, I gotta go ahead and build this roof and some new steps.", and he just go over there and knock it out on the weekend.

Jamaal: Just go ahead and do it and she fix him some food, bring him a plate while he out there.

Rashaun: Sweet tea, a little chocolate cake or something, that was how everything was set up. It was like a, you know, it's kind of a trade system because we have like, my great grandfather had like four or five pecan trees in the yard and boy, he would have us out there picking up the pecans and he would sit there and bag them up and he'd put them in a car man, everywhere he went when he saw a friend, he would give him a bag of pecans like, "I just got these out the yard.", and it was like that community vibe, that type of give and take, where everybody was trying to help each other.

Jamaal: Yeah, because in a lot of it is like, yo, I remember my pops used to-- we used to find blackberry bushes and so I was like, man, we take these, we're gonna get some blackberries, it's like, yo, put these up, I'm gonna take them over here and see if I get her to make me some cobbler, some blackberry cobbler, you know what I mean? Like, it's that type of thing, where it's like, it's not just yours. It's ours. Like, all of us like you get some, you jump out to get some peanuts from the side of the road, we've talked about pulling up in a truck, you pull up in a truck, open a trunk, it's like yo, trash bags of peanuts. Like, yo, we gonna have some peanut, about to roast some of these peanuts up, right? And it's just like, you never know what the day was gonna be, like you just wake up-- you wake up thinking you just going to sit around the house like next thing you know you roasting peanuts, playing ball. You know, it's a good living man, people might be sick of listening to us like, reminisce like that but it's not often I get to talk to somebody that been there, you know what I mean? We been on the streets with the bike, you know. Riding for like five miles just to go to the store, give me a hug and I'm happy.

Rashaun: We used to play basketball on the red clay.

[Cross talk]

Rashaun: And the ball was-- we played so much that the grass was gone, and the clay was super hard.

Jamaal: It's cleared out. Yeah.

Rashaun: And bro, we used to play on a goal that was attached to a tree.

Jamaal: You got to man, I had a bungee cord attached to my tree to keep the pole up, man because the pole's-- my man Antoine dunked too hard one time and he bent the thing out of the ground so, we had to attach it to the tree.

Rashaun: Yeah, we'll be out there playing and man, you would come in with your shoes and it's like your shoes will be straight red because you've been out there playing in the red clay and man, that's all this show was about. It was-- I was telling somebody that this was me really giving my flowers to the place and to the people.

Jamaal: So, we talked about that red, one of the characteristics in a lot of these prints and some black and white but some had this great, man, this awesome red color that you put into it, man, how did you get that color, and kind of talk a little bit more about the significance of it.

Rashaun: Man, well, I knew I wanted to-- man, I had the name for the show, Up from the Red Clay for like over a year. I knew I wanted that to be the title and I knew I wanted to incorporate red some kind of places but I want to say, I'm pretty sure that it was an old Margaret Burroughs print that I saw that had like a little slice of red in it and it made me think like, "I need to try this, I need to see how this is gonna work on a large scale when I'm putting like, you know, these flat reds in there with a black on top.". And the funny thing was, I couldn't really find a lot of examples like that when I started so, I started looking at paintings, started looking at drawings or other things that were incorporating red and black like that and I was like, "This might work.". So, by the time I started the first one, which was, Burdens Down, I was like, "Man, this is like intense, I gotta keep this going.". So, I did that, and I knew like immediately, like I needed the monoprints, the monotypes to be red and I knew when I wanted to put a drawing to it, I needed to use red pencils for the drawing as well because I wanted to keep with that theme throughout the show.

Jamaal: Right. And I think it's interesting how you chose to not carve the red at all, like you used it as just a straight flat background, no details, no second level of nothing inside of it. Like, why did you figure to do that? Just a straight, simple two colors? Because the red and I'm gonna interject one minute, but the red, when you print it, I'm looking at The Ghost of New Bethel right? It's the hand with the church fan with MLK on it and when you look at it, that red is so overwhelming. Like, it joins the whole piece, it just floods it almost so, that to me is a stylistic choice, but explain it a little bit to me.

The Ghost of New Bethel linocut by Rashaun Rucker

Rashaun: That is definitely a stylistic choice, I wanted the red to just merge with the black. I really, even though it's a two-color print, I thought of it as one color, that's how I was thinking about it. So, like, I don't want to carve anything into this red, I just want it to be flat and I just want the red to push the black even further, and this is really the first time, for anybody who knows my work, you know, my print and my work, not reuse color ever.

[Cross talk]

Rashaun: Black and white, old school.

Jamaal: I'm with you, man, I did the same thing, man. I only just started dabbling with color because there's something so striking about it, man. Like, we talked about a little bit about the simplicity of just a black and white image, like, what can you do? How can you make value with just black? You know what I mean? So, part of it is the challenge at hand and the look that you get, this kind of graphic look. But another thing is, like, were you using black, and I did this for a long time, using black as a cipher for blackness, right? And how we relate to each other as a people.

Rashaun: I think it was probably for two reasons for me, for it to represent blackness and then the second reason was it always added like a graphic novel nature to it. And, you know, huge was comic book fan and huge, you know, I mean, at the core, I might be-- some people, it's funny, some people here in Detroit, identify me as an illustrator because I think even some people when they look at the printmaking, they're like, "It's got such a graphic striking look to it that it looks like, it would almost be like a magazine cover or like, that type of vibe.". The black is always used, you know, for a second reason, just I love the way like, you know, how, why is his name escaping me now? The dude behind Sin City and you know--

Jamaal: Frank Miller.

Rashaun: Frank Miller. Frank Miller's work always kind of struck me and so, that was another reason I kind of just like the simple black and white processes of printmaking.

Jamaal: And I can see how it can get to, especially because you're telling these narratives, with your pieces, it can seem like illustrative, like, think of a piece from the show, The Procession, right? Where you have the man like, holding the casket up. Like, that seems like a story is implied because you're focusing on all the activity that's going on at a wake, like you're focusing in on these two particular events, it feels like there's a story behind, like, why they'll focus on, who is it and kind of what was this funeral that was going on.

The Procession linocut by Rashaun Rucker

Rashaun: Actually, it's funny, because that was the one thing that is not a photo reference, those are actually from my kind of memory. The person in the rear is me when I was about 18, or 19 and I've been a pallbearer for all of my grandfathers' funerals. So, both grandfathers and my great grandfather, I've been a pallbearer. And just in that mindset of like thinking about, you taking somebody to their final, you know, resting place on earth, you know, I always just think about, like, you know, carrying them, but I also think about how many times they carry me as a person because my grandfathers were so intrical in my upbringing.

Jamaal: Yeah, that's powerful, man.

Rashaun: And it's the same way, when you look at The Coronation piece like, I think, me having 20 years as a journalist, I think my artwork does have a narrative storyteller aspect to it. Because I just, I spent 20 years of my life telling stories through photographs. And so, that's why I'm kind of not surprised when people just kind of identify me as an illustrator. Because it's like, I know it does have like illustrative qualities to it because I'm always trying to tell a narrative.

Jamaal: One piece in the show that you got, Before the Throne, that's one of the drawings in the show, right? So, this one is definitely built for narrative because you have these two, some of these are your grandparents.

Rashaun: Great grandparents.

Jamaal: Yeah, great grandparents just sitting on the chair like you know, everybody's seen a chair like that at the house too. You know, you get that chair like that, you hide cotton, you know? Like, "Man, where you get this chair from? That's nice.", it probably still got the plastic on it.

Rashaun: Yeah, it was one of those 80's floor and it's funny because they were actually at my grandmother's house, which is their daughter, doing a Christmas in the early 80s, that's where the photo reference came from. But plenty of my grandparents-- my great grandparents in that picture had a couch similar to them, but theirs had plastic on it and they had plastic runners all through the house, everywhere through the living room because you didn't go in living room unless it was a holiday. That was not a room to sit in.

Jamaal: They don't want you to mess up the floors, man.

Rashaun: As we say, you know, what you're doing in the front room? You don't be in front room unless you got people over. And the reason I called it Before the Throne because they were like, the royalty of our family, the matriarch, the patriarch, I feel like people spent their whole lives just trying not to ever embarrass them. So, when I saw that picture, it was like, such a stately pose on that floor couch and they were kind of holding hands and it was like, "Man, they look like the king and queen.", atleast, they're my king and queen. So, that's how the title came about, Before the Throne.

Jamaal: How many kids did they have?

Rashaaun: Five.

Jamaal: Five, okay. Yeah.

Rashaun: Which really ain't even a big family when you think about it back in the day.

Jamaal: I mean, that's how many in my family and I consider it to be a nice size.

Rashaun: To me, it huge but you know, back in Warrenton, people had land and they were farmers, so you know, my grandma's like, "People having kids just for help.".

Jamaal: Yeah, yeah. I believe that.

Rashaun: You know, you see families with like, eight and nine kids, it's like, they be the help on the farm.

Jamaal: Yeah. My wife got-- her grandma had 13 kids. I think her father had like, another 10, like they have a huge family. Like, they take up a whole section of Infield, not Infield, of Emporia in Virginia. So, like, it's all them areas man, it's like, you live there, you know, and these are the people that's there man, I think you captured their stories like, well, man, like it's amazing. Tell me about, I'm gonna dabble into these monoprints right quick. Tell me about the feelings about the monoprints because they have a completely different feel and if you all see them, make sure you go check out Rock site and check out these mono prints. I find them striking because there's a sharpness to like every other piece and these monoprints aren't just about the flow. Just about, like imagine if you just you stepped in some mud and like you just make a footprint and like you see an image inside of it, that's what I think of a little bit when I look at it. Like, tell me about the process of making that and kind of switching your mind frame because it's no level of detail and you are big on detail, right? Like, you get all into all the nooks and crannies of faces and all that kind of stuff and now you have these very loose kind of circular pieces. Tell me about it.

Rashaun: Well, I think one of the things I wanted to do was, I've always been fascinated with painting, even though I'm not a painter by any stretch of imagination, like I've never even really dabbled in painting. And I was like, "Man, I want to kind of like stretch myself a little bit.", and the first thing you think about the playmaker doing these monotypes because you can get like a painterly effect and it was the first time I've done one since college and it was you know, I wanted to do something that had a real immediacy to it, what do you just like, I'm gonna paint this on this plexiglass, put it's paper on it and then pull it off and then whatever's there is there. Because like, there was barely any ink for a ghost image you know, some people make those prints, like I didn't even do the ghost prints because like there was so little ink left on the plates. But I wanted it to be something where you just got a feeling for it like, I just want you to feel the-- and it don't have to be perfect. And you know, so that was kind of my approach with it and I was like, and also, I'm real particular about giving our community access to fine art so, whenever I have a show, I always want to do a small, you know, some smaller pieces for people who are just beginning to get into art, and want to start their collection. So, the monotypes is one of the things, it was like it was a twofold win, because it was like, I could experiment in ways I needed to but I could also give access to our community because at some point as an artist, like it always kind of bugged me, it's like, you got to make a living as an artist, but at some point, a lot of times, our work will get to prices where like the average person can't buy it.

Jamaal: Yeah, that's true.

Rashaun: And it's like, I kind of want to always have something like that for like people to have access because I know growing up outside of, you know, my two cousins who are artists and like me, my family wasn't buying art, we didn't have no money for that. You know, nobody was going out. I think the first time somebody in my family bought something, was the charles bills and it was like a plant, it might have been like $700 and that was a ton of money.

Jamaal: Yeah, that's a lot.

Rashaun: So, you know, if you're like thinking about people like your work start getting a four or five figures, the higher you go, the smaller the circle of people who are there and have the ability to buy it.

Jamaal: Yeah, and the further outside the community you gotta go.

Rashaun: Exactly. So, you know, shoot, I want the dude who drive the bus to be able to buy something just like the real art collectors. Like, I want to give him a pathway to becoming a collector as well, you know? And then, sit in the house and be like, "It's real artwork in house.".

Jamaal: Yeah. And it feels a little different because also the subject matter, a lot of these are just singular people almost like the one Papa Chuck, tell me about Papa Chuck and kind of what it meant.

“Papa Chuck” monoprint by Rashaun Rucker

Rashaun: That was my grandfather he passed away a few years back, but we always call him Papa, his first name and everybody else called him Chuck, you know, if you knew him, he would be like Mr. Chuck or whatever, but we called him Papa. So, I just kind of combined two names, Papa Chuck but his signature look was always a trucker hat with the Aviator glasses. So, my grandma saw, you know, it's like, she was like, "I knew that was Chuck as soon as I seen it, I saw that hat.", you know, and it was always the old school trucker hat with a little string across the top, the little rope and he always had like big aviator glasses. And just, you know, just paying homage to people who like, really constructed my foundation as a human being.

Jamaal: Yeah, good people, man.

Rashaun: Good. He always, you know, he never called me by my name, he always called me slow motion. All the grandkids had nicknames and mine was slow motion. He's like, "Man, you ain't never in a hurry about doing nothing.". And I mean, I'm kind of just that, that's the type of person I am. Because I remember one day like I said, my great grandfather in Warrenton, he had a landscaping business and he employed like a ton of people in the family and just some people who lived in Warrenton, and he had-- he left me in a lady's house to cut her grass one day and he came back to pick me up and the lady was paying him at the door and this particular lady had a huge yard and she wanted her yard to be pushed, she didn't want rides in her yard, she wanted it to have a line like a baseball field. And I'll never forget it man, this lady, is an older white lady, this lady and this is like such a Warrenton, southern thing, it kind of like pissed me off but this lady made some tea bro and sat at the patio table and watched me cut her grass. She had a mini cheese sandwich, her sweet tea and literally, she was fanning herself, she was watching me cut the grass and I was like, by this time I'm 15 or 16 so, I'm thinking like, "Man, this some old roots type of stuff going on.". But I was just cutting the grass at my pace because I wanted it to have lines and all that stuff. When my granddad came back because he went to another job site, he came out to get me and load equipment up and she paid him, I guess they were talking, I got back in the car, he said, "That lady asked me-- she told me that she didn't even think you were moving at one point.". Like, what? "You was cutting the grass so slow.", and that's all-- everything we talked about, it was wrapped up in this show, and it's just a lot of love. And so, you know, when they got home that day, and I told you I saw for the first time, FaceTimed my grandmother who's in her 80's, and it's like, I was kind of like, "Man, she might not even hit the FaceTime button.", because sometimes she won't answer and hit the FaceTime button but she did and I walked her through the gallery man and like she started crying as soon as she saw the first piece.

Jamaal: That's awesome, man, that's gotta be a good feeling.

Rashaun: Bro. I was like, at that point, I don't give a damn about nobody buying nothing. Like, you know, I already hit the mark, you know with my grandma so, you gotta think about you know, I always tell artists, you can't make work to sell, like, you got to make work because you love it, think of it as a thing where it's like selling only your number one point because it is like, you got to make something that means something to you.

Jamaal: That means something and that makes it mean something to other people, right? Because you put enough love into it, that she felt it, you know, just by the idea that and you know, art is about representation too. So, just the idea that she never thought probably of herself as being the type of person that would be in artwork.

She's in two pieces, and that's like one of the big payoffs for me because the largest piece in the show, she's in that piece and that piece was bought by Wake Forest University for their permanent collection. So, I'm like, "Man, my grandma, my great grandfather's in there, my dad is in that quilt piece, Tapestry of my Soul and my great grandfather, he only finished the second-- the sixth grade.". And I'm like, I'm thinking in my mind like, "This is dope because my family, particularly my great grandfather, who didn't even get to go to school, because he had to work is going to be in one of the most prestigious academic universities in the country.". And I say, when I'm dead and gone, some kid gonna be walking by Tapestry of my Soul, looking at it in a library or wherever it's gonna hang so, I was super excited when they called about it, and it just won because it's my hometown in Winston-Salem, and it's like family legacy, and, you know, looking through the catalog, and it's like, it's gonna be in there with an Lan Lygon, at Whitfield Lovell and it's gonna be in there with amazing artists, you know.

Jamaal: That's good company.

Rashaun: And I was just kind of like, "Man, my grandma gonna be in there.", and everybody dead and gone bro, that printmaking quilt gonna still be there.

Jamaal: That's awesome, man.

Rashaun: And that's what it's about, that's what legacy is about, you know.

Jamaal: That's real legacy right there.

Rashaun: Yeah, you know what else I think bought this on? I was telling him I didn't really think about it in the beginning of it but I think COVID had a you know, a part-- played a part in this because I hadn't seen my family, I still haven't seen them for like, over a year. We haven't travelled and, you know, my mom got diagnosed with breast cancer during the COVID and surgery and, you know, have her breasts removed and had to go through all this by herself during COVID, and, you know, just her and my stepdad. And I was kind of like, "Man, COVID, if nothing else, it made you really realize like how fragile life was and why people pass from COVID.", and watch people just lose family by the drove and it kinda was like, "Man, you know, I always had this idea of honoring my family, but like, what a time to do it.".

Jamaal: Yeah, the perfect time. I think it's amazing how sometimes, like you say, you would think about this probably for a while, but it lined up in just the right way, in just the right moment, for you to be able to make all the work that you did, because who helped you print it? Like, somebody, who helped you print it? Because let me tell y'all, I always tell this Ruck, this guy, "You gotta get off your floor, man.". This guy is so DIY, he's so Warrenton, this guy's like lining up his mono cuts with the floorboards for registration. Like, this dude is amazing, like, it's amazing that you ever get anything printed bro, I'll tell you the truth man, it's awesome. However, you got some help for printing this time, who helped you print?

Rashaun: So, I gotta give a shout out. So, I did the monotypes and all the other-- some of the smaller stuff in my house but normally, like you said, I just print on the floor and Jamaal and everybody else I know been clowning me for years because I've been making additions on like two and three, because it's like, when you're printing with a doorknob on your floor, you can't make 25 prints. Yeah, you can but it's hardcore and I'm not going to that level.

[Cross talk]

Rashaun: So, you know, I've been working, the last couple of projects I did with printmaking, I ended up doing, you know, AP to creativity and working with Lee Marshall on this, who was a master printmaker, here. So, I worked with Lee on this project, and it was funny because, she was still like, "Dude, you're working with a printer now, you still making additions in three.". I'm like, "This is who I am.", because she was like, "We can make 10, 10 is respectable.", she was trying to convince me. You know, Melanie would always say, at the gallery, she's like, "Man, you're still doing those super small runs.", but I always just kind of want to keep it that way to make them precious and it was like, especially with this because this is my family. So, I want to keep it precious, and I want to know where they were going. Like, this is going to a place that I can like, go see him if I want to or you know, just know they going to a good home. Yeah, Lee is like incredible man like, I've been working with her for over like the last year like, you know, we will continue to have a full-fledged relationship, you know, throughout my pride-- she used to be the master printmaker, sigma return here, but now she's o her own.

Jamaal: That's what's up.

Rashaun: So, you know, she specializes in lithographs, but we have yet to venture into that realm.

Jamaal: I think you would do great with lithographs, man.

Rashaun: Man, she's always like, "I can't believe you ain't never done lithograph. She's like, "That's write up somebody's alley who can draw.".

Jamaal: Yeah, that's right, especially like you get that graphite look that you got, like man, you want those crayons in your hand? You'll be straight man. Like, it'll feel like you're drawing on paper, like on your stone. I think you would kill it, that need to be on your list like immediately.

Rashaun: It is on my list for the things I'm gonna do within the next year.

Jamaal: Yeah, I think you'll do good.

Rashaun: She got a ton of brand-new stone so, she like, "When you're ready, let me know.".

Jamaal: So, are you gonna stick to this two-print thing for like the rest of your career? Like, this is what make you legendary. Like, can't nobody get your prints, they got to line up like, get on the waiting list for the next project.

Rashaun: I mean, at max, I only ever see myself making five, max.

Jamaal: That's dope man, because I've limited myself to 10 like, 10 is kind of my number. Like, if I'm like extra good, like To Be Free, I printed 19 of them like that's a lot for me. Like for me, that's a whole lot, yo, I don't-- I'll tell people that I got kind of ADD or sometihng because like, after I print like a couple of them, it's like, I'm done. Like, I don't need to like, print the whole run.

Rashaun: That's the same thing, it's also not me, wanting to be precious, which I do, but it's also my joy is in the carving and I think all my happiness is in the carving. So, once it's carved and I print a couple and I see them, then I'm done. I'm ready to move to the next carving. I think that's probably- -because I always tell people like, you know, and I think I've told you this before, like I tell people because they laugh about it, I say, "Man, what you see on the gallery wall, that's the residue of my joy, that's not my joy, you're getting the residue, my joy is in the carving and the drawing.".

Jamaal: Yeah, that's the stuff I got to do to make money, that like the good stuff that you know, in the studio just thinking about it, you know what I'm saying? That's the fun stuff, figuring it out because you're always right there, man, you kind of get a good anxiety because it's like, the next thing I do can completely trashed his whole piece or it can make it you know, belong in a MoMa somewhere.

Rashaun: Yeah, and that's a damn thing too. Like, I was talking about making work and selling, I think you also got to not may work just because you feel like, you know, you can't make work and be like, "Oh, I'm gonna make this because it's gonna go on for a institutional collection.", you got to really just make what you love and how you feel, you got to you know, make the right work for you. Like, I'm never making work like, "Oh, my God, one day the DIA is going to buy this.", I can't wait on their validation.

[Cross talk]

Rashaun: You know, and I always had his belief, you know, maybe because it comes from Warrenton and my great grandparents, you know, always had this belief that time gonna reveal everything, you know, if it's meant for you, it's gonna be meant for whether it's now, whether it's 10 years from now. You know, my grandma used to tell me, you know, "God got to wear a slow walking you down.". So, at some point your time going to come and then, until then you just do the work. You know, I always think about the interview you did with Debra Roberts when she talked about working in the shoe store and then when she won the polygraph, people started coming away. She was like, "I had a ton of work because I had been working with no recognition for decades.". So, that's why I tell people, I'm like, you see these stories about these like, high artists and these meteoric rises, and I'm like, "Well, you can be a meteoric rise when you like 60 or 50 or something like that. Like, no, you just discovered me, bro. I've been doing, this.". And I always think about that with Dox Thrash, I got his book in my house and it's like rediscovering America math. I'm like, "How the hell you rediscover somebody who been here?", like Dox Thrash been making dope printmaking work, it just so happened that he died and y'all saw it. I was talking about this the other day with Charles White, he had these big retro statues that went to Chicago and there was a MoMa and all those other places. I told him, "I retrospective of Charles White's when I was in college, in the 90s', in a black college.", I said, "Y'all just now seeing his work, I've been a Charles White stan.". He been my art idol forever since I was in college, that's been over 20 years.

Jamaal: Was he a heavy influence on you? Like, even-- he did printmaking too so like--

[Cross talk]

Rashaun: Man, he is my guy, he's my number one art person. I always tell people, I think him, Whitfield Lavale, Margaret Burroughs, the Jacob Lawrence, growing parts kind of make up my tribe of artists that are like my ancestry or tribe that I like really influenced heavily by, love them. I think as we look at a lot of my drawings like, you can see the direct inspiration from Whitfield Lovell and his work, definitely with my bird work, same thing with Charles White who like, and also for my printmaking, where it was Charles White, Kaitlyn Boroughs, but I would also give a big nod to Hale Woodruff as well. A lot of my background market like in Procession are very similar to how he used to make marks

Jamaal: Yeah, that's good stuff, now you get to be mentioned in that same breath man. Like, we out there man, trying to make it to the next level, right?

Rashaun: I mean, with contemporary American printmaking, I look at you and Alina, Latoya Halves, En Johnson, it's a lot of people I look at and I'm inspired by Steve Prince. You know, it's a ton of great contemporary, black printmakers out here.

Jamaal: Yeah, we all connected somehow.

Rashuan: We all kind of know each other at this point, which is awesome, too.

Jamaal: Yeah. Well, let them know where they can find you, man.

Rashaun: Man, I'm on Instagram @ruckerarts and rashaunrucker.com is the website. So yes, man, I'm like super excited to be back home Studio Noize, making some noise, back on here with my family, back on here with the family of listeners that I love and how many people I introduced Studio Noize to.

Jamaal: We appreciate it bro, I appreciate it, that's why we here, man.

Rashaun: I get that question a lot, "Where can I find a great, black art podcast?", I'm like, "Oh, my boy has got the one.", it might be the only one as far as I know.

Jamaal: It's the only one they need, the only one they would need, we'll have everybody here eventually. It is Studio Noize man, the voice of black art, that's what's it gonna be, man.